Our problem is that we have made the family (or marriage) into a more holy and fundamental sphere of life than the church, but the New Testament sees things very differently. Very differently.

I don't like that that might be a problem, but is it?

Thursday, June 23, 2011

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

The Perfect Body

Our natural eschatological hope is in the perfect body, free from scars, faults, asymmetry, limitation, and unable to be rejected. It gets what it wants. We are bombarded by glimpses of this future hope. We trick oursleves by watching this world from the outside and naming it "fantasy" and naming our watching "escape", thus creating the illusion that we can watch and not participate; that we are still the ones who hold the power; that we really do live in the real world and are free to come and go from it as we please. without consequence But our eschatological hope defines what is really real in the world. What we name as fantasy is ultimate reality, of which our faulty, asymmetrical, rejectable bodies are shadows. We are indelibly shaped by our vision of the "perfect body". Everything we do aims towards that glorious future. And if we cannot attain it in our lifetime, we will worship those who can.

Our supernatural eschatological hope is also in a body, but a body with scars.

Our supernatural eschatological hope is also in a body, but a body with scars.

Sunday, June 19, 2011

Another Trendy Christian Video

This one -- complete with "overwrought and ever-present" soundtrack -- feautures Stanley Hauerwas, whose laugh is as infectious as his words. Selected quote:

Also, is it just me or does Hauerwas have a similar accent to Heath Ledger's Joker?

Being a Christian should just scare the hell out of us.

Also, is it just me or does Hauerwas have a similar accent to Heath Ledger's Joker?

Saturday, June 18, 2011

An Uneasy Christian

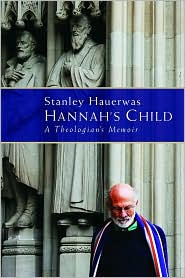

There are only a handful of books that I have wolfed down. Improvisation, The Reason for God, The Prophetic Imagination, **cough** The Da Vinci Code. I read quite a lot, but I read slowly, and I like to have several books on the go. But as soon as I started reading Hannah's Child: A Theologian's Memoir by Stanley Hauerwas, I left aside every other book. When I got the urge to read, Hannah's Child was on the receiving end, and no other.

As a young man, it is his experience as a young man that stayed with me throughout the memoir. Hauerwas could not come to think of himself as a Christian, despite his Christian heritage and dedication to Christian learning. This experience enabled me to name my own: I am a Christian, but I have no idea what that means. Well, "no" is an overstatement, because after glimpsing the life of Hauerwas and friends, I'm beginning to understand a little of what it means when he declares at the end of the book, "I am a Christian". And I can see what I see in Hauerwas in the people I see as Christians amongst family and friends. I just could not name it until now. It is called love.

There is much else I could write, but a passage from the book will say it all better than I could. It is a wonderful example of the way Hauerwas thinks, and the way he relates. The setting is a round table discussion between faculty members.

There were probably fifteen of us. We introduced ourselves to one another by describing what we studied. The biologist talked of his fascination with butterfly wings. Barbara Herrnstein Smith made clear why relativism is true. A biochemist described the research he hoped would have therapeutic outcomes. I was one of the last to speak. I began by confessing that some of them might not regard me as a proper academic because I was not a free mind. Rather, I served a church that told me what I should think about. I offered the example of the Trinity, noting that, as far as it is possible to do so, I am suupposed to think about that. I then observed that it is clear to me who I serve, or at least who I am supposed to serve. I concluded by asking my colleagues who they thought they served.

We had a good discussion, but they did not address my question. The next day, however, I ran into Frank Lentricchia from the literature program. In fact, we met in front of Duke Chapel. Frank and I had come to Duke at the same time, but I did not know him well. I was drawn, however, to his naturally abrasive character. Frank said, "I've been thinking about your question. I know who I serve. I serve myself." I responded, "God, Frank, I hope that doesn't mean you have to do what you want to do." Frank recognised a sermon when he heard one. Drawing on my experience at Notre Dame, I told Frank that with a name like Lentricchia he had to be a lapsed Catholic. I suggested that he needed a priest and that I knew just the one - Mike Baxter, one of my graduate students.

The three of us had dinner. Frank, in his inimical way, asked Baxter, "What have you been up to?" Mike said that he had just gotten back from a retreat with the Benedictines at Mepkin Abbey. "Really," Frank asked, "what was it like?" Mike said simply, "They were happy." Frank replied, "I have to go there." He did. The rest is history, as Frank himself later recorded it in an article in Harper's. In ways that are not entirely different from me, Frank will probably always be an uneasy Christian, but hopefully God takes pleasure in our unease.

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

Wolves and Horses

Yet another piece of evidence in the case for The Wire as a contemporary prophetic voice. Here is the wisdom of Omar and its prefiguration in Scripture:

How you expect to run with the wolves come night when you spend all day sparring with the puppies?

- Omar

If you have run with footmen and they have tired you out, then how can you compete with horses?

- Jeremiah

Monday, June 13, 2011

Evangelism and Social Action

Patrick Mitchel of IBI, MCC, and "friend of Scot McKnight" fame has begun a series of posts on the gospel and social responsibility over at Jesus Creed. Check the first one out here. A similar topic was mentioned to me over the weekend, with someone saying that the view of one prominent Chritian leader is that evengelism and social action must be distinguished but joined together. This is my initial response to that view, jotted down on the train back to Belfast and very much open to being shaped/changed by Patrick's series on Jesus Creed.

Evangelism and social action. To distinguish between them is to do evangelism an injustice. For evangelism is social action. To speak the language of good news is to act in and for the world as a social being among other social beings, witnessing to the possibility -- indeed, immenence -- of a new social reality and existence.

Before Moses led the children of Israel out of Egypt, he spoke. Not to pharaoh, but to pharaoh's slaves -- Yhwh's people. Moses's words constituted a social action. His bringing of good news -- his evangelism -- created a new social possibility in the midst of the old one. The days in pharaoh's brickyard were numbered. Scripture tells us that Moses spoke the words of Yhwh to Israel in Egypt, and Israel in Egypt believed and worshipped Yhwh. The liberation has already begun. The social action of Yhwh in coming down to his people and the social action of Moses in evangelising to his people has begun it.

Rather than retaining the sanctity of evangelism by distinguishing it from social action, the distinction merely highlights our increasing distrust in the language of faith. Or perhaps more seriously, we no longer even know what the language of faith is. We no longer know it as language powerful enough to do something, to create newness in the thick of injustice. We have distinguished between evangelism and social action because we have distinguished between the gospel and history. The gospel has come to concern our life post-history, thus distinguishing it from the historical work of social action. But when the two are thusly distinguished, it is unintelligible and incoherent when they are inevitably joined together. The writers in Transforming the World seem to perpetuate the confusion by speaking of salvation as "practical as well as spiritual" (emphasis mine). Is spiritual salvation impractical? Is practical salvation unspiritual?

If we are to break the divide between evangelism and social action, we must recover the word of the LORD proclaimed by Jesus and witnessed to by those who followed him: The kingdom of God is at hand. God is at work in Egypt, bringing Israel into a remarkably new existence. God is at work in the world, bringing the church into a remarkably new existence. And near the beginning of this work stands Moses, who received from Yhwh good news and who shared that good news with a people in desperate need of it. This sharing was a liberating social action -- an event that called out of slavery a community of worship and hope. The kingdom of Pharaoh was at an end. The kingdom of Yhwh was at hand.

Of course the liberation was not complete after the evengelism. But neither was the liberation complete after the crossing of the Red Sea. The work of liberation, of salvation, was ongoing. It always is, until God is all in all.

Sunday, June 5, 2011

Dog On No God

In week five of The Apprentice, one team produced and marketed a brand of pet-food called "Every Dog". The philosophy behind the brand was simple: manufacture a product that can be sold to as many dog-owners as possible. Own a labrador? Try Every Dog. Own a poodle? Try Every Dog. Own a rottweiler? Try Every Dog.

The creators of Every Dog would not stop there, however. Their plans were global, with the "Every" series reaching out to cats, goldfish, hamsters, and possibly even humans one day if all goes well. "Every Human: For every day, there's Every Human. Now available in North Korea."

While the goal of creating a food suitable for every dog proved to be unattainable, the philosophy behind the project is surely in step with the age we live in: appeal to as many as possible, monopolise the market, make people's choice the same as everybody else's.

With that in mind, allow me to formally introduce you to the latest brand that has swept across the globe at an incredible rate. It is called Every Worship. "For every Sunday, there's Every Worship". It shares the same philosophy as its pet-food counterpart, but the difference is that this brand can be (in fact, has proved to be) a huge success. Go to any local church and the chances are you'll experience the generic, universal delights of Every Worship...though it must be said that some churches are much better at it than others. There is a science to it; a formula to be followed. But there is no art, because art is particular. There is no art, because art is cultural, and Every Worship suppresses culture.

What we don't hear about amidst the subtle takeover that Every Worship has achieved is the cost -- the opportunity cost -- of its hegemony. What does Irish music sound like in Irish churches? What particular words do Irish men, women and children have to sing to their God? We do not know, because most of us have drunk deeply from the Every Worship well, and in doing so have forgotten that we can drink from our own.

What's more, attend an Irish church and hopefully you will be joining with people from tribes and tongues that are foreign to these shores. That is part of the gospel's beauty. But by consuming Every Worship, we have created an easy unity through cultureless worship, and thus tamed the explosive power of the gospel to create a diverse community out of strangers. What if, instead, our worship was expressed through all the different cultures that participate in it? It would be clumsy and awkward for a few and for a while, but it would be rich in meaning and artistry and truthfulness. It would be a taste of new creation, creating an undomesticated understanding and unity between diverse peoples as only the sharing of our musical and lyrical heritage can create.

This is particular worship, participated in by particular people in particular times and places.

Every Worship must be named for what it is - the suppression of cultural diversity, creative artistry, and particular truthfulness. In other words, the suppression of what the church is called to embody.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)